This is a dish that most certainly would not have made it onto my Irish Catholic mother’s childhood dinner table, and yet it regularly found its way onto ours growing up, courtesy of her husband — my father — and his Eastern European heritage.

The dish, correctly known as haluski, happens to be the national dish of Slovakia…who knew?!

Unlike my paternal grandmother Baba, my mum was neither fluent in Slovakian nor Slovakian cooking. She was, however, determined to try to learn to make her new husband happy(ier). She likely learned the Slovak word for cabbage – kapusta – from the many dishes in which the star ingredient appeared regularly at family gatherings on my father’s side. Kapusta this, kapusta that, always with the kapusta. Learning how to make halupki (stuffed cabbage) the Slovak way with my father’s idiosyncrasies baked in (no onions!) was a mean feat for a skinny girl from the Irish section of Bayonne. And so, in our family, she named the dish kapusta and forever shall it be in my own kitchen.

Having said that, and with a very quick Google search, one learns that kapusta and haluski are actually rather interchangeable, depending on which country and which cook is promoting the dish. Additionally, there are as many variations of the dish as there were appearances by Slovakia in the Ottoman Empire during the late 17th century, so, basically, lots and lots.

My mother must have been dismayed early in her marriage to learn that she was not going to have the luxury of depending on fish for meatless Fridays in our Catholic household. Dad was not much for fish, nor were their two progenies.

I imagine, in my head, that in those first years of marriage, she would have marched herself over to her devoutly Catholic mother-in-law’s house to find out what, in fact, the golden boy would eat on Fridays (that would be my father, only son to a mother who believed that the sun rose and fell with him and brother to two older and bossy, but doting sisters – his words, not mine…)

Mom turned out to be a quick study, likely due as much to her intelligence as it was to her estimated bandwidth of tolerance in taking direction from a drill sergeant…that would be my grandmother.

It was during lent that this dish rose to fame in our Ohio household, a state to which we moved when I was in elementary school. Many hours’ drive away from our hometown of Philadelphia, and without a Google box, my mom relied on her memory of those lessons and her creativity to make this particular dish.

While other dishes regularly made it into our Friday evening meal, things like meatless spaghetti bakes, grilled cheese, baked potatoes and salad – kapusta was a treat even on non-Fridays, and on those days was often fortified with bacon, always doused with copious amounts of parmesan cheese.

Traditionally, haluski is a humble dish consisting of nothing more than lots of butter, sautéed cabbage and onions, salt and pepper, and then tossed with medium-wide egg noodles. The medium-wide sizing of these noodles was a non-negotiable. My father would turn his nose up at a dish that contained wide egg noodles like a cat does a cucumber. (Have you Googled cats and cucumbers? It is a baffling phenomenon.)

The problem was that medium-wide noodles were not easily found back then. How did Eastern European families get them, then? They made them, of course! I don’t think I ever ate a store-bought noodle as a young girl when we visited Baba. I highly doubt my father thought one could actually purchase them in a grocery store until my mother quickly dampened any hope he might have had that she would become a noodle-making maven running around with an apron festooned to her waist.

No, my mother worked full time and making noodles was not going to be happening in her household unless her husband wanted to try his hand at the endeavor.

Instead, she sought out medium-wide noodles at grocery stores that specialized in items from the old country and when she could eventually find them in a regular grocery store, she broke the news to my father that his days of home-made noodles were over, unless he’d like to go home to visit his mom more often. Let’s just say, he learned to love those store bought beauties.

One more note on the importance of medium-wide noodles, at least to my dad. One of the last dishes I made for him before he went into the hospital in the last year of his life was kapusta. Despite having made the dish for him many, many times, he never forgot to remind me when I announced what I was preparing for dinner, “Don’t forget to use medium-wide noodles, Christine.” As if.

I laugh now because the dish, under my mother’s tutelage, became rather unrecognizable as a Slovakian dish. She Helene-ified it and frankly made it memorable and insanely delicious. What was simply braised cabbage and onions and butter before – and good on anyone for whom that is completely and utterly fine – became something altogether lip-smacking different in her kitchen.

It should be noted, my mom was not a cook — and she came from a long line of non-cooks, as well. My Irish grandmother could make a mean potato seven ways to Sunday, but past that, her culinary skills (and interest) were of limited use. Living so close to New York City and having a favorite uncle there who regularly would spoil my mother with dining out in his favorite haunts, she grew up knowing how to navigate a fine dining menu. She knew a good dish when she tasted it, but to cook one? She let others shine at that particular skill.

But, then came my dad and his heritage full of foreign favorites which forced her to learn at least some dishes he loved from his childhood. And, drill sergeant or not, his mother was the one to teach her. So, she learned the basics, “made them her own” as she liked to say, which usually meant quicker, tastier, and truth be told, rather unrecognizable as an old world dish. It did not hurt that her in-laws lived 700 miles away because I am not sure her modifications would have been held in all that high esteem.

For example, my Baba used to rinse sauerkraut before she used it in things like halupki. In fairness, this was probably done because she made her own sauerkraut and that required lots and lots of salt. (She also baked her own bread, made her own pizza, and probably cured her own ham, for all I knew.)

But, my mother, who could certainly not imagine why anyone, ever, would make their own sauerkraut when there was a perfectly nice jar at the grocery store waiting to be purchased, admonished me to never, ever rinse the sauerkraut. EVER. “You’ll wash all the flavor out!”

She would add garlic where there definitely would never have been. Parmesan cheese, too, made a regular appearance in most any dish it might prove a benefit to, which, of course, meant most dishes.

Kapusta was no exception. Braised cabbage? Nope, not in our house. Instead, it was roasted until sweet — seriously, caramelized cabbage is the only way to go. Other variations over the years may or may not have included a splash of wine, a drizzle of tamari, a sprinkling of French thyme, many (many) cloves of garlic, and always, always, loads of parmesan.

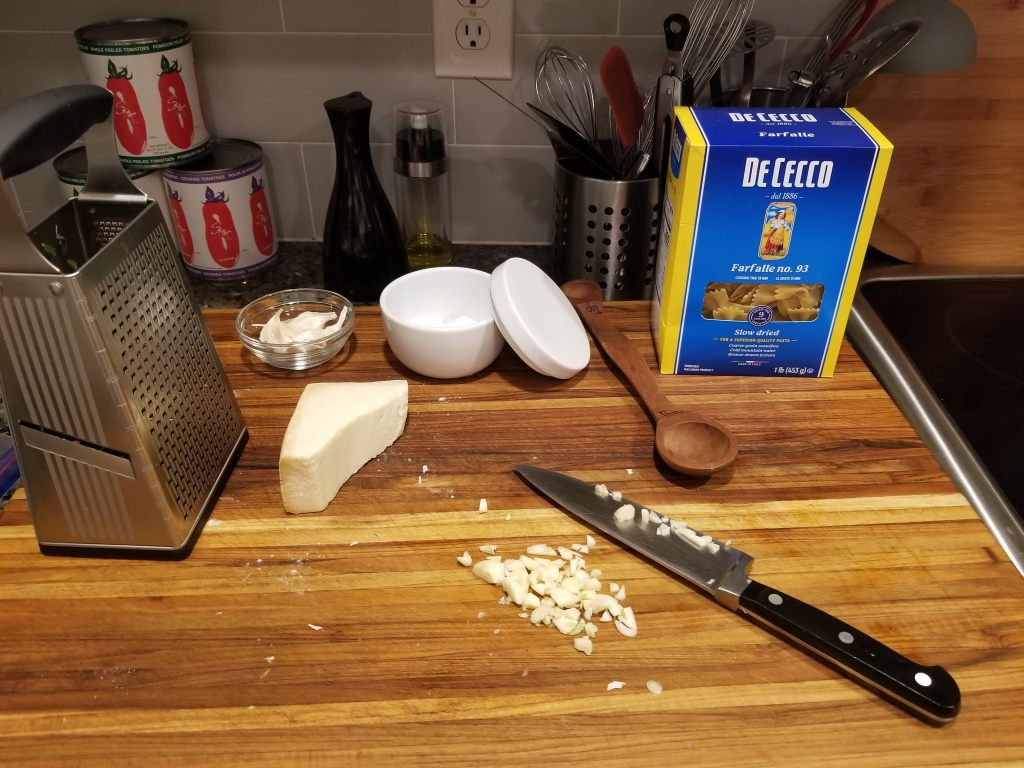

About those medium-sized egg noodles? Well, they went out the door the minute I took over the recipe. Farfalle is far prettier and has abundant nooks and crannies to capture all the goodness. Thank goodness my parents are no longer around to witness this blasphemy…

There is no recipe to go along with the photos – the ingredients are what they are: cabbage, butter, noodles, onion. Whatever else you choose to add will just be between you and your maker, but if your Baba is still kicking, you might want to hide the evidence.